The road travelled and the road ahead: Anwernekenhe 6 keynote address

The road travelled and the road ahead: Anwernekenhe 6 keynote address

HIV Australia | Vol. 13 No. 3 | December 2015

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this article of HIV Australia contains names of people who have passed away.

By James Ward

Werte! Let me begin by paying my respects to the traditional owners of country in Mbantua, to their elders both past and present, to Helen Liddle and your extended family – thank you for welcoming us all here on country.

To our other Elders in the room, let me pay my respects to you. Alice Springs and its surrounds is a special place for me, it is where my family’s ancestors moved and roamed for thousands of years before me.

In writing this speech, I have reflected and pondered what it means for a community organisation like Anwernekenhe (the ANA) to turn 21.What has been? What will be? The road travelled and the road ahead.

However, allow me to start a little earlier than Anwernekenhe. I want to begin by going back to 1982.

October 1982 was the year the first HIV case was diagnosed in Australia. After much mayhem and scary media on a daily basis, AIDS was about to get us all, fear was instilled in us all – especially a dreaded fear instilled in gay men.

It’s probably fair to say that Australia and the world was facing a public health issue it had not seen before. The economy of Australia wasn’t that strong, and much effort was put into thinking how we as a community could address HIV.

There was no doubt that HIV had caught the world off guard. At this point we were all flying blind. 1982 was also a time when black Australia was finding its way in an Australia that had denied our forebears so much since colonisation.

It was only 15 years earlier that the 1967 Referendum was held, allowing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be included in census counts. It was clearly a time when Aboriginal people were finding our feet after an extended period of the White Australia policy.

It was a time when much angst existed between our two populations, and furthermore, in our extended GLBTI communities, racism and class were pervasive, and some still see that not much has changed in this regard.

We were faced with a new disease that was having devastating consequences on the people we loved. As a population we were still struggling to regain our rightful place in Australian society.

During these early days of HIV in Australia, much work was put into preventing HIV among particular populations – particularly marginalised groups like sex workers, drug users and gay men.

In recognition of what HIV could do to these groups it wasn’t long before a response was mounted. In 1986, led by Dr Alex Wodak, Australia’s first needle-syringe program (NSP) was trialled in Sydney. By testing returned syringes, this pilot project found an increase in HIV prevalence, suggesting that HIV was already spreading among injecting drug users.

In the following years, NSPs became policy throughout Australia as governments realised the provision of sterile injecting equipment was essential to reducing the spread of HIV, in addition to hepatitis B and C. It’s clear now that NSPs have saved thousands of Australian lives.

Medicine and science has made some wonderful achievements in HIV. On a global scale it’s now thought that by the year 2020 – five years away – 90% of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status; 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART); and 90% of all people receiving ART will have viral suppression.

This is what’s known as the ‘90-90-90 strategy’ – what amazing ambitious leadership and what amazing advances in science. However we have to be very mindful that our communities don’t become the 10% that are left behind.

On the treatment side we have moved from a single anti-cancer drug AZT in the early days, to the highly active antiretroviral treatments available to people living with HIV today, and now with drugs even now able to be used to prevent HIV.

The drugs in the early days were horrendous, the side effects noticeable, and although AZT was available, it wasn’t easily available and it wasn’t nearly half as efficacious as today’s drugs are. I have very close friends who were doctors at this time, who spent copious hours filling in paperwork to get medicines prescribed to patients – not as a right, but on the grounds of compassion.

Thankfully, we have moved on.

Now it goes without saying, that many of us have lost our friends, our lovers, our colleagues, our family, and our community members. Australian society is weakened without these people here; they were warriors of their time, and if science was as advanced as it is now they would be still here. They were all taken far too young, far too early, and often, in the prime of their lives.

For those of you who survived that period, what amazing people you are, what amazing souls you are, and we are forever grateful – you have so much to share. For you to have seen and lived the suffering, to have felt the loss, to have feared and faced your own mortality, what incredible souls you have, what incredible guardian angels you have looking over you.

The beauty of science has made life for people living with HIV easier too – unlike the first decade and a half of HIV in Australia, where our fellow brothers and sisters living with HIV had no way to hide their condition; you would’ve no doubt seen it in movies or on your TV screens in features like Philadelphia, The Ryan White Story, or, in our context, Holding the Man.

In those days, people living with HIV were so visibly recognisable by their condition – wasted bodies, the obvious karposis carcinomas. Today it’s almost impossible to tell if someone has HIV or not.

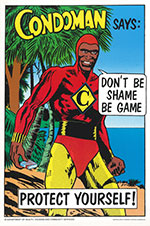

So that brings me to focus on the Indigenous response – and let me begin with our famous Condoman who first came to light in 1987 by a group of Indigenous health workers in Townsville. The campaign sought to promote and encourage condom use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

The popularity of Condoman has increased over the years. The campaign used humour and messaging that impacted the population it touched on the taboo subjects of sex and injecting.

Prompted by the Grim Reaper ads a year earlier, Prof Gracelyn Smallwood advocated for Commonwealth funding because she feared our mob would miss out on the messages seen on TV then or not make sense of the Grim Reaper ad.

Our own leadership was strong, if you go back to the 1989, when the first ever National Aboriginal Health Strategy (NAHS) was launched. The leadership group who wrote NAHS clearly knew what effect HIV/AIDS could have in our communities.

It outlined strategies for Aboriginal Health Workers to be skilled up in prevention, as well as strategies for testing and treating and caring for people living with HIV.

1994, just a few years later, and Anwernekenhe’s birth occurred in Hamilton Downs some 120kms up north east of here; a roundtable of sorts, a gathering of minds, a gathering of leaders, coordinated by my good friend Phil Walcott (who incidentally still lives here in the Alice) and the late John Cross. And so the journey began of Australia’s community-led response to HIV by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Many of you were at the Anwernekenhe 1 conference, and some of those at this first meeting have passed on, and some are not able to be here this week to celebrate.

And so, here you are today 21 years later at Anwernekenhe 6, pondering the path ahead and celebrating the past, which was grim for some in those early days, best demonstrated by the late Prof Fred Hollows in 1992 when he spoke at the first ever National Aboriginal HIV/AIDS Conference here in Alice Springs, and argued that some areas of the AIDS campaign were being inadequately dealt with at the time.

In his work he had observed the spread of AIDS in contemporary African communities, and he was concerned that AIDS would spread as vehemently through Aboriginal communities.

Gladly, we are testament that that hasn’t been the case but it doesn’t mean he was wrong! The chances of this happening are as real today as they were then.

Our survival has been strong, the emergence of community orgs such as Outblak was born 20 years ago – a gay and lesbian social group in Melbourne that was developed to provide a space for gay men and their friends in Melbourne, and is still a great community event in Melbourne.

For me personally, a lot has changed. I have been involved in the development of the HIV response – particularly in this setting – for many years. I remember working here in Alice Springs in the late 1990s, creating video tapes in central Australian Aboriginal community languages about HIV.

ANA’s role in the past 21 years has been focused on responding to the community, developing campaigns for the community, supporting staff working in mainstream organisations, advocating for change within AIDS Councils, supporting the development of policy and practice, membership of national committees within the HIV partnership.

It’s an important role, and one that needs to be continued. It’s unacceptable that right now that ANA, like many other community-based organisations, are struggling with long-term funding commitment from governments.

So what does the future hold for us as a community? I am here to say this – if we are not careful we will end up with rates of HIV similar to African countries like Nigeria.

So what does the future hold for us as a community? I am here to say this – if we are not careful we will end up with rates of HIV similar to African countries like Nigeria.

You might ask ‘Why?’ My response is because it’s happened in similar populations to us, such as in First Nations Aboriginal people in Canada. Let me just point to one province in Canada, Saskatoon, where the rate of HIV is equivalent to a rate of HIV in Nigeria.

Saskatoon is a prairie province, and 16% of its population is Aboriginal. The province has over 600 cases of HIV, in which 80% of them are Aboriginal and 75% of which have been driven by injecting drug use. Because of the high rates of HIV in Saskatoon, the healthcare system is struggling to help all the people affected.

This is very possible in Australia, as we have a similar healthcare system and have seen similar scenarios in the past on many other health conditions. Back in 1998, Australia first started collecting epidemiological data about cases of HIV in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community.

We have had collectively about 600 cases of HIV diagnosed in our population over the years. The rates of HIV have been on par with the Australian population for most of that time, but in the last few years the rate of HIV diagnosis has been creeping above the non- Indigenous population.

It’s worrying, it’s concerning, but we have failed to get this up in national priorities. People, I hope one day, will see the risk. It would be much wiser to respond now, rather than once something has happened.

So what do we need to do to prevent this from happening?

To me, we have a handful of issues that require strengthening in our response. The first of these is the high rates of other STIs that exist in many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island communities.

With over 50% of young people living in remote communities diagnosed with either chlamydia, gonorrhoea or trichomoniasis, we need to do something urgent and drastic to reduce these rates. It’s well established that if you have another STI it makes it much easier for HIV to be transmitted – this is of major concern.

On the subject of other STIs, right now in Australia and among our people, we have the largest syphilis outbreak recorded for over 30 years. This outbreak started out from an initial few cases in Queensland and has now spread to over 800 cases in northern Australia, spanning three jurisdictions.

This outbreak mostly affects young people heterosexual people. We have much to learn from this syphilis outbreak – but the main point is if we don’t get on top of HIV quickly, once it’s diagnosed in communities we will be up the river without a paddle.

We must do more to control STIs in our communities; it’s unacceptable, it’s appalling – our people deserve better. I don’t think we are all that prepared for outbreak responses once HIV is detected in communities.

The second area of HIV prevention that needs strengthening is in the area of injecting drug use (IDU) within our population. With 16% of all cases of HIV diagnosed over the last five years in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population attributable to IDU, something is going wrong in our population.

We have new drugs like ice; we have risk factors never contemplated before; we have contestable ideas about harm minimisation programs in communities – we need to be doing more.

The third area is through the transmission of HIV from regions on Australia’s doorstep. PNG is on the doorstep of the Torres Strait Islands (TSI), and the TSI are on the doorstep of Cape York – an entry point to the rest of Australia. We need to do much more in this space.

Another area we need to do more about is our work with gay men. Survey data have shown differing risk factors in both sexual risk behaviours and injecting risk between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and non-Indigenous men.

The emergence of sistergirl and brotherboy communities also raises issues into the future about risk prevention strategies.

So too for people living with HIV – the new science of starting people on treatment as soon as possible is compelling for better lives and healthier outcomes. How can we ensure people within our communities are tested, diagnosed engaged in care, on treatment and attain a sustained undetectable viral load?

Finally, we need to address stigma and discrimination. There is a subtle type of discrimination that exists in our communities, sometimes between black and white, sometimes between HIV positive and negative, sometimes between non-drug user and drug users, sometimes between gay and non-gay, and sometimes between genders.

Stigma and discrimination drive risk, and we must make these connections and tackle these issues head on. There is much that needs to be done in this space and ANA is ideally placed to tackle these issues.

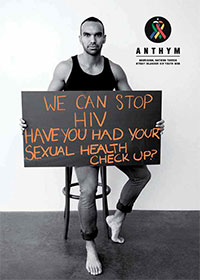

ANTHYM poster. Read about ANTHYM.

The establishment of ANTHYM (Aboriginal National Torres Strait Islander Youth Mob) is great for our sector – a desperately needed. We desperately need to find a space within the response for ANTHYM.

If we could do all of these things well – and do them now – then HIV would still be one of the best stories in Aboriginal health in another 30 years.

The prevention toolbox comprises more than just condoms now. Of course, condoms are a mainstay in prevention efforts; however, treatment is now considered a major tool in the prevention toolbox. The science is clear; the earlier you start antiretroviral treatment the longer you will live.

If you are on treatment, the science is that you can enjoy a life with an undetectable viral load, and once again enjoy sexual liberation with your loved ones.

PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) offers us great opportunities again to enjoy the sexual freedom we once enjoyed. This is promising; however, we need to stop and consider and challenge what this will mean to a community with already STIs at too higher levels and nuance the messaging around this to make sure we don’t escalate STIs in our urban and regional areas.

Similarly, HIV rapid tests are an incredibly welcome tool to the HIV sector.

ANA’s role in the Australian response is real, it’s one that is needed, and it’s one that needs to be supported. The mantra of ‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ is pertinent.

ANA is made up of representatives of the community affected by HIV and this community conference is important not only as an update for you, but for the rest of your communities.

History tells us now more than ever we need to change. We need to review our efficiency; we need to review our effectiveness; we need to tackle HIV prevention differently.

We need to ensure our services that we expect so much from can deliver what is expected of them, and what is required of them in delivering on clinical guidelines.

Because, despite all the advances in science and all the knowledge in the world, a cure for HIV is not yet in our scope.

We need to be sophisticated in our approaches. We need to be on top of what is happening in our communities.

We need to be alerting people what the story is in our communities – because responding afterwards is too late.

In closing, I want to acknowledge the contribution Michael [Costello-Czok] has given to this component of the approach within our communities.

It’s a milestone that has to be celebrated. Your commitment is commendable. I know it hasn’t been an easy path.

Finally, in closing, it would be remiss of me not to mention two others: Neville Fazulla and Rodney Junga-Williams.

Connected through kin, connected through blood, I love you both dearly. I miss you like crazy, Rodney, and I am sure you are watching down us today and would be ever so proud of both of our efforts.

And to Neville, you’re the essence of bravery, courage, strength, love and compassion. I know you work tirelessly, and I know you’re committed. I want to acknowledge your efforts, not only at this conference, but over the last thirty years. You’re a star. And on that note, thank you.

Listen to James Ward’s complete Anwernekenhe 6 keynote address

Associate Professor James Ward is Head, Infectious Diseases Research Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health at South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI).