Lyle Chan: an AIDS activist’s thoughts on music, history, and creativity

Lyle Chan: an AIDS activist’s thoughts on music, history, and creativity

HIV Australia | Vol. 12 No. 3 | December 2014

By Jill Sergeant

Today, Lyle Chan is an acclaimed composer, whose works have been commissioned and performed by major artists including soprano Taryn Fiebig, pianist Simon Tedeschi and the Sydney Philharmonia Choir, and the even former Foreign Minister, Bob Carr.

Today, Lyle Chan is an acclaimed composer, whose works have been commissioned and performed by major artists including soprano Taryn Fiebig, pianist Simon Tedeschi and the Sydney Philharmonia Choir, and the even former Foreign Minister, Bob Carr.

But in the early nineties, Lyle was a core member of ACT UP and other AIDS organisations. He and fellow activists couriered AIDS treatments from the US that were unavailable in Australia, fiercely lobbying the Australian government to approve experimental treatments more quickly.

But in the early nineties, Lyle was a core member of ACT UP and other AIDS organisations. He and fellow activists couriered AIDS treatments from the US that were unavailable in Australia, fiercely lobbying the Australian government to approve experimental treatments more quickly.

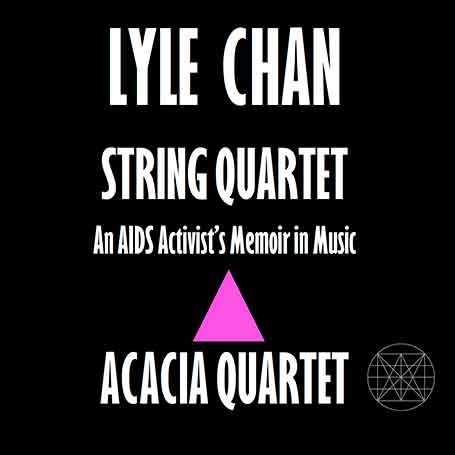

During this time, although Lyle says he’d ‘given up music to be an activist’, he continued to sketch music – his way of documenting emotions during the ‘crisis years’ of Australia’s HIV epidemic. Twenty years later, Lyle developed these musical sketches into a composition which became known as String Quartet: An AIDS Activist’s Memoir in Music. Lyle then partnered with Acacia Quartet to bring this work to the stage.

On the eve of several performances which took place in Melbourne during the week of AIDS 2014, Lyle spoke with AFAO’s Jill Sergeant about the memoir, activism, and the value of music.

Jill: This piece of music was a long time in the making. You say on the program notes that it started out as diary entries back during your days as an activist in Sydney in the early 1990s, but you only completed it very recently.

Lyle: In 2010, I was asking myself a lot of questions about what I wanted to do as an artist. I realised that to be able to focus on composing, I had to get past the experiences of the early nineties, and I remembered that I had my diary entries.

Now I call them diary entries; I never thought of them that way back then. I was just sketching music that related to the feelings I had at the time. Sometimes there were just a few bars, and sometimes, like in the case of the work that I wrote after Bruce Brown died, it was virtually performable as it was.

Bruce was the poster-boy for Sydney activists … a lot of people wanted to join ACT UP to make the change that Bruce spearheaded. He was a professional musician. He was very inspiring in that he gave up a job in order to be an AIDS activist … I have friends who were Wall Street traders who did the same thing. There were not that many full-time activists and Bruce was one of them, and it was truly, truly inspiring thing to remember that people actually made great sacrifices to bring about changes like accelerated drug approval.1

You’ve written essays to complement the musical pieces. Did you write the text at the time you were doing the musical sketches?

I didn’t keep a diary in words. The dates would tell me what a piece was about, if I needed any sort of reminder. But after I turned each sketch into a performable piece, I would write something so that the performers or I would have something to speak on stage. I’m still in the process of writing the full length versions of those essays, and some are available on my website.2 But the music certainly came first.

How did Acacia Quartet get involved?

Acacia had played another piece of mine, unrelated to the AIDS Memoir, and they wanted to play more of my music. I gingerly showed them the piece about David and they played it.They found it very hard, both emotionally and technically. Then they said to me, ‘there must be more, right? Surely there is more.’ I said yes, there’s probably about eighty minutes more. So they said, you keep finishing it and we’ll keep playing it.

The next section I wrote was about Franca Arena and her twin sons.3 Acacia played that and got a good reception from audiences. In fact, their concert at the Melbourne Recital Centre for AIDS 2014 was booked a year ago on the basis of one person hearing that section.

Then Acacia wanted another section for a concert in Brisbane, so I wrote the first section of Dextran Man, which was about Jim Corti, and after that it snowballed.

How closely do you work with the musicians?

In this particular case, quite closely. As the composer I would have a way of hearing the music in my head and I would expect them to play it that way, but of course my notation being limited, as all notation is, they would play it the way they hear it and sometimes I would think, oh wow, that’s a better idea. So the music is completely written by me but we worked on the interpretation together.

There will come a time when the music leaves me. There will be performances of this music that will not involve me or Acacia. In the same way that Shostakovich’s music is played today by people who have never known him, they just know the tradition of its playing. I want that. I want people to bring whatever they think, whatever they feel to the music.

Were the Acacia Quartet’s suggestions and interpretation purely based on how they were responding to the notation as musicians or were they also related to the history you had already told them about?

I talk to them quite a bit because they have been genuinely very curious. It will be interesting for them when they do these performances during AIDS 2014 because they will meet people in the audience who knew the people they are playing about.

To Acacia, people like Bruce Brown, Tony Carden and David McDiarmid are almost mythological creatures, they are just like names in a novel, but when Acacia play in Melbourne [during the week of AIDS 2014], they will meet someone who was present at Bruce’s death. It will be a level of reality beyond just knowing me.

They play this fourteen minute piece about David’s health and his care and his activism, but they never knew David. They will be performing surrounded by his artwork at the National Gallery of Victoria.

A lot of the stuff that they have brought up was based on responding to the stories. Sometimes they wanted to make things more explicit than I wanted to and I would say ‘just trust the notation, you don’t have to exaggerate that. The message will be clear, if you play it in the subtle way that it is written rather than needing to punch home the point’.

The piece Towards Elysium was written after AIDSX published the Self Euthanasia Recipe. It was the most blatantly illegal act that we had done and Acacia, in the early performances, really wanted to emphasise what they felt was the journey of the soul into eternity and to play the music in some way to reflect that. I felt it was in a way distorting the music. The music was lucid and if you play it in its simplest form that feeling comes through anyway.

A lot of the stuff they worked with me on was technical. My last memory of Tony Carden was playing the organ at his funeral, so there’s a passage that sounds like church music. They weren’t thinking, ‘let’s make it sound like an organ,’ but rather they were thinking, ‘how do we phrase and slur it so that we bring out sweetness in the sound?’ That’s where I really appreciate their input. That was something I couldn’t do.

Was grief one of the things that kept you from completing the sketches and has revisiting them helped you to deal with the grief from that era?

Having finished writing this memoir, I’m experiencing a feeling of saying goodbye to the period. I don’t know how to answer your question because I wonder if I have ever actually grieved. I think one of my responses to people dying back then was frustration more than grief. We were in a war so you moved on to the next skirmish.

Maybe I don’t see the point of grieving. I respect the memory of all my friends who are not with us and I show my respect in ways like writing pieces about them. Maybe that is grieving. I don’t feel sad actually. I wonder if once upon a time I might have and I don’t remember. I am just honoured to have known them and in some ways a memoir like this is to give a voice to people who are dead.

Have you thought about what pieces the Acacia Quartet will play at the launch of HIV Australia and the AIDS Education and Prevention journal, at the G’day Networking Zone at the AIDS 2014 Global Village?

It will be a noisy environment, and a lot of the music is soft and contemplative. To exclude that would not give the right impression of the work. We’re going to see if we can amplify Acacia so they can play Towards Elysium, which audiences love.

The opening of Dextran Man4 is also good for an audience who is hearing the music out of context. It’s quite a powerful story and I don’t think it’s being told anywhere else. It’s about Jim Corti and how he illicitly manufactured ddC. About four hundred people got ddC from me back in ‘91 and ‘92 and I couldn’t tell them where it came from. I’m not the person they should be thanking, it’s Jim Corti. I would like to play that piece at the launch because there is a history to be respected.

Where do you think you will be in a few years’ time in terms of your music, or do you have something already on the horizon?

I think all art is a journey into the unknown. As an artist, if you know where you are going to go then you’re making something, but it’s not necessarily art. I have lots of commissions that I have to fulfil.

I am presently writing a piece for the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS), who commissioned me to write a work for their resident ensemble. Their animation students will make a film based on it. I also have a choral piece to write for a choir that’s going to Europe next year. They’re playing in a couple of famous Abbeys and they want to take an Australian piece with them.

I can only write a piece of music I believe in. Life is too short to do otherwise.

You can hear the music of Lyle Chan at www.lylechan.com

References

1 Quote taken from ‘Activism and creativity: Kirsty Machon in conversation with Lyle Chan,’ a presentation given at the G’day! Welcome to Australia Networking Zone during the 20th International AIDS Conference, July 2014, Melbourne.

3 Chan, L. (2012, 8 August). Mark and Adrian are her sons (1991/2012) from String Quartet. Retrieved from: www.lylechan.com

4 Chan, L. (2012, 4 October). Dextran Man, Part 1 (1991/2012) from String Quartet.

Retrieved from: www.lylechan.com

Jill Sergeant is Project Officer at AFAO. An extended version of this interview appears on the blog, AFAO talks (afaotalks.blogspot.com.au)