HIV and sexually transmissible infections among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: summary of the latest surveillance data

HIV and sexually transmissible infections among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: summary of the latest surveillance data

HIV Australia | Vol. 13 No. 3 | December 2015

By Marlene Kong and James Ward

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program was established at The Kirby Institute in 2007.

The Program works collaboratively across sectors to close the gap in health disparity between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous people, with a key focus on sexual health and blood borne viruses.

Each year, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program collaborates with the Surveillance Evaluation and Research Program on the Bloodborne viral and sexually transmitted infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: Surveillance and Evaluation Report.

The surveillance report provides information on the occurrence of blood borne viruses and sexually transmitted infections among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia for the purposes of stimulating and supporting discussion on ways forward in minimising the transmission risks, as well as the personal and social consequences of these infections within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

This article has drawn information from that report to provide a summary of the latest surveillance data pertaining to HIV and sexually transmissible infections (STIs).

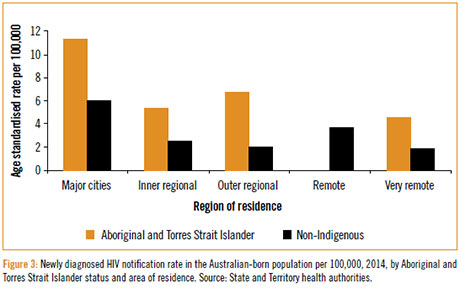

Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population continues to be overrepresented in notifications of STIs, and blood borne viruses (BBVs). In particular, outer regional and remote communities continue to experience substantially higher rates of notifiable STIs.

The information that follows is a summary surveillance data related to STIs and HIV recorded for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities for the period 1 January–31 December 2014.

HIV

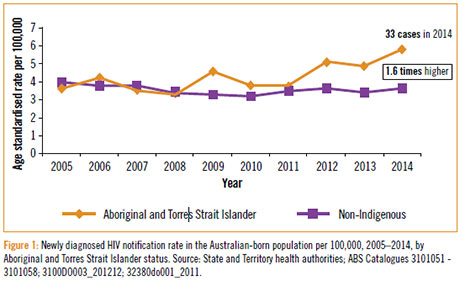

There were a total of 1,081 notifications of newly diagnosed HIV infection in 2014; 33 diagnoses were among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (Figure 1).

242 cases of HIV infection were newly diagnosed in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in the ten years from 2005 to 2014.

Between 2012–2014, the notification rate of new HIV diagnosis in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (5.9 per 100,000) was higher than in the non-Indigenous population (excluding people from a high HIV prevalence country of birth) (3.7 per 100,000).

The notification rates of newly diagnosed HIV infection in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population are based on small numbers, and may reflect localised occurrences rather than national patterns.

Among notifications of newly diagnosed HIV infection in 2010–2014, the most frequently reported route of HIV transmission was sexual contact between males in both the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (50%) and non-Indigenous population (75%).

A higher proportion of notifications from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations were attributed to injecting drug use (16% vs 3%) and heterosexual contact (20% vs 13%) and in females (22% vs 5%), as compared with the non- Indigenous population (Figure 2).

Based on tests for immune function, a third (30%) of the new HIV diagnoses among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population were determined to be late, in that they were in people who had their infection for at least four years without being tested.

In 2014, HIV prevalence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples was similar to the Australian born non Indigenous population (0.11 vs 0.13%).

The higher rate of HIV diagnosis in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the past five years requires a strengthened focus on prevention in this vulnerable population (Figure 3).

Chlamydia

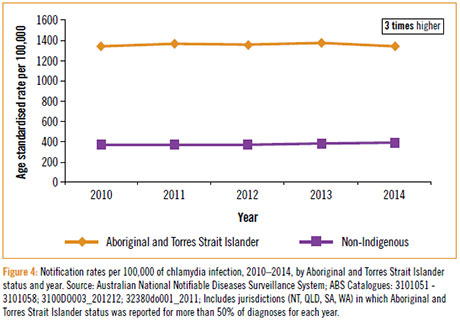

Chlamydia continues to be the most frequently reported condition in Australia, with 86,136 notifications in 2014.

Of these, 6,641 (8%) were among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population; 25,365 cases (29%) were among the non-Indigenous population; and for 54,130 (63%) diagnoses, Indigenous status was not reported.

Over the last five years, chlamydia notification rates in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population have been around three times higher than the rate in the non-Indigenous population (Figure 4).

Chlamydia predominantly affects people aged 15–29 in both Indigenous and non- Indigenous populations, with the highest notification rates occurring among women in the 15–19 year age group.

This may reflect greater disease burden, and/or higher rates of access to health services and subsequent testing in these populations (for example, antenatal screening in the younger child-bearing population pyramid of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population).

Despite just 22% of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population residing in remote areas, chlamydia notifications reported from these areas accounted for more than half of all notifications in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (Figure 5).

Gonorrhoea

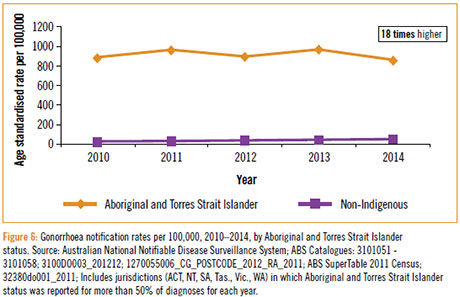

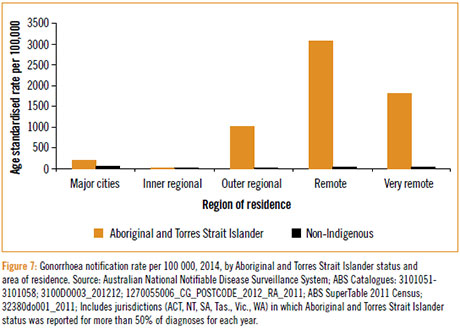

Of 15,786 notifications of gonorrhoea in 2014, 3,584 (23%) were among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population; 6,915 (44%) were among the non-Indigenous population; and for 5,287 (33%) notifications, Indigenous status was not reported.

The rate of gonorrhoea notifications in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in 2014 was 18 times higher than in the non-Indigenous population (Figure 6).

71% of cases among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population were diagnosed among people in the 15–29 year age group, compared with 56% in the non-Indigenous population (Figure 6).

For the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, gonorrhoea is mostly diagnosed among young women and men living in remote areas, while the majority of cases of gonorrhoea in the non-Indigenous population are among gay men living in major cities.

This creates two distinct gonorrhoea epidemics in Australia, each of which requires separate responses (Figure 7).

Infectious syphilis

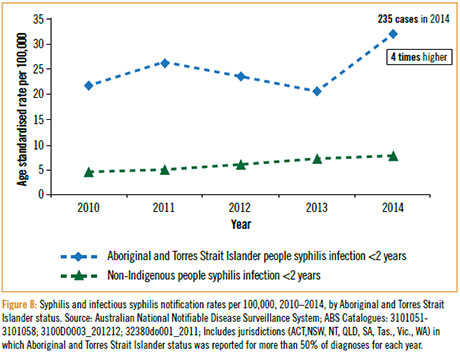

Nationally, 1,999 cases of infectious syphilis were diagnosed in 2014; 235 (12%) among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population, 1,588 (79%) among the non-Indigenous population and Indigenous status was not reported for 176 (9%) diagnoses.

The notification rate of infectious syphilis in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population in 2012 was four times higher than the rate in the non-Indigenous population (32 vs 8 per 100,000 population) increasing to 300 times higher in remote areas (Figure 8).

Rates of infectious syphilis notifications among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population increased in 15–19 year olds in 2011 (from 34 per 100,000 in 2010 to 95 per 100,000 in 2011), due to an outbreak in the northern areas of Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia, and was 99 per 100,000 in 2014 (Figure 8).

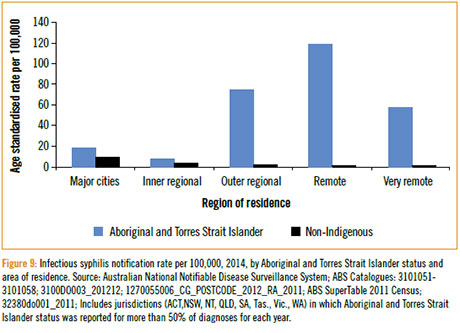

Like gonorrhoea, infectious syphilis affects two main population groups: young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and men equally in remote communities, indicating predominantly heterosexual transmission; and gay men living in major cities suggesting that transmission is primarily related to sex between men.

Notifications of congenital syphilis in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples declined from seven in 2005 to one in 2009, and then returned to 5 in 2014.

The resurgence of infection in remote communities after years of declining rates, bringing with it cases of congenital syphilis, emphasises the need for testing and treatment in this population, particularly in antenatal settings (Figure 9).

Donovanosis

Donovanosis, once a regularly diagnosed sexually transmissible infection among remote Aboriginal populations, is now close to elimination.

After a peak in the late 1990s and early 2000s, no cases were detected in Australia in 2011; only one in 2012; zero in 2013; and one in 2014.

Implications for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities

Rates of STIs are particularly high among both Indigenous and non-Indigenous young people living in outer regional and remote areas of Australia; however, it is important to note that rates of chlamydia notifications are higher across all geographical locations for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population compared to the non-Indigenous population.

Two distinct epidemics exist for gonorrhoea and syphilis and urgent action is required to address levels of knowledge, community awareness and understanding of STIs as well as promotion of testing as a prevention strategy in these communities.

In addition, further resourcing is required to assist health services address the burden of disease in these communities.

Internationally, high rates of STIs in communities implicate higher HIV notification rates; however, so far this is not the case in Australia, where rates of HIV diagnoses among the Indigenous population have been comparable to the non-Indigenous population; however, the trend in recent years of higher rates of HIV occurring in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population than non-Indigenous Australians is worrying.

The stigma surrounding HIV continues to be a key driver of HIV transmission, undermining HIV prevention efforts.

STIs can also have significant physical, psychological and social consequences, especially for young people, who may shy away from seeking health care.

Addressing stigma and bringing STI rates under control – particularly in remote Aboriginal communities – should remain a national priority until they are at least comparable to the rest of the Australian population.

Finally, ongoing efforts to improve access to needle and syringe programs and other harm reduction programs are required to reduce HIV notifications caused through injecting drug use. To achieve this, further efforts are required to ensure equitable access to:

- education and health promotion in school and teenage years

- effective and well-resourced clinical health service delivery, and

- effective prevention strategies such as needle and syringe programs (NSPs) and opioid substitution therapy (OST).

For further information, see the Bloodborne viral and sexually transmissible infections in Aboriginal & TSI people: Annual Surveillance Report 2015.

Dr Marlene Kong is Program Head, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program at the Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia.

Associate Professor James Ward is Head, Infectious Diseases Research Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health at South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI).