Drug policy and criminalisation: more harm than good

Drug policy and criminalisation: more harm than good

HIV Australia | Vol. 13 No. 1 | March 2015

By Ele Morrison

As a young volunteer in a drop-in centre for drug users in Yunnan Province, China, I was advised that above all I was there to ‘do no harm’. It was some of the best advice I have ever been given.

Harm reduction is, as the name implies, an approach that is meant to reduce harms associated with using drugs. It realistically recognises that punishing people for drug use, drug dealing and drug trafficking will never be able to stop illicit drug use completely.

Instead, it includes the provision of injecting equipment and opiate substitution programs like methadone with the main aim of reducing transmission of blood borne viruses such as HIV and hepatitis C.

Harm reduction services have been provided in Australia for almost thirty years and are still one of the most effective health programs ever put in place. In Australia alone, tens of thousands of hepatitis C and HIV transmissions have been prevented since the services were first rolled out.

As well as saving lives, harm reduction is also cost effective: for every one dollar spent on needle and syringe programs, twenty-seven dollars is saved in health care costs.1

The same harm reduction models are now used all over the world. Most countries with a recognised population of people who use drugs (PUD) have some sort of harm reduction program, often funded by donors like the Australian Aid program.

Harm reduction has been successful in every country it has been established, even when it is small in scale.

And yet, criminalisation continues to be our primary response to drug use – even in Australia, a proud exporter of harm reduction expertise.

Two-thirds of the funding for responses to drugs in Australia is given to law enforcement, and most of the drugs that were illicit in 1986 are still deemed illicit (only marijuana has been decriminalised in some states2). In many countries, the situation is worse.

Some countries with harm reduction services rely entirely on international donors to fund them, while they are more than happy to put money into policing, prisons and, in several Asian countries, compulsory drug detention centres.

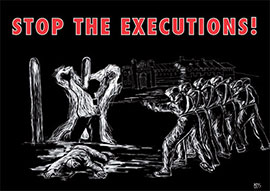

AIVL campaign poster protesting the use of the death penalty for drug offenses in Indonesia. A vigil was held in Canberra on 18 February, 2015. Illustration by John Carey

AIVL campaign poster protesting the use of the death penalty for drug offenses in Indonesia. A vigil was held in Canberra on 18 February, 2015. Illustration by John CareyIncarceration, and fear of incarceration, are some of the most significant harms that come from using illicit drugs.

People who are afraid of being arrested are less likely to access health and harm reduction services and report stigma and discrimination when they do access these services.3There are many consequences of this.

People who use drugs in Australia access health services less than other sectors of the community, are more likely to access health services only when their health issue has become an emergency, and have unacceptably high rates of sharing and reuse of injecting equipment.

In 2013, approximately 24% of people participating in a national NSP survey reported re-using needles and syringes and approximately 16% reported using a syringe that had been used by someone else – figures that are likely to be under-reported.4

Incarceration has a significant impact on the health of the people imprisoned. Since 1999, at least ten countries and sixty prisons in Europe, Central Asia and Iran, have implemented a range of models of providing injecting equipment to inmates.5

They have found these programs to be overwhelmingly positive. There have been no cases of prisoners using injecting equipment to threaten guards and there have been reduced transmission rates of HIV and hepatitis C within the prisons.6

Evidence from ten studies in prisons with needle and syringe exchange in fact shows improved safety for prison staff related to injecting equipment.7

In Australia, as in other prisons around the world where injecting equipment isn’t supplied, prisoners still inject drugs, they just don’t have new and clean equipment with which to do it.

This makes sharing of injecting equipment common by necessity, and consistently Australian and international studies report higher levels of exposure of hepatitis C, hepatitis B and HIV among prisoners.8

While the prevalence of HIV and hepatitis C in Australian custodial settings is low, it is higher than in the community as a whole. For this reason people in custodial settings are identified as a priority population in Australia’s National HIV Strategy, Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy and Hepatitis C Strategy.

However, despite this recognition of drug use in prisons as a priority issue for blood borne virus prevention and despite Australia’s reputation as a ‘world leader’ in harm reduction, there is still no needle syringe program or needle exchange in a prison in Australia.

In 2008, the Alexander Maconochie Centre was opened in the ACT. It was promoted as Australia’s first ‘human rights prison’ with the idea that rehabilitation, rather than punishment, would be the focus.

Included were plans to establish Australia’s first prison-based needle exchange, in line with the United Nations charter stating a prisoner’s right to receive the same standard of health care they receive in the community.

The ACT government has been in full support of the establishment of a needle exchange inside the prison.

Katy Gallagher, the former ACT Health Minister and Chief Minister, championed its implementation in the lead up to the 2012 election, saying:

‘There are some significant implementation decisions to be sorted out, but I’m not here to warm a seat. I’ve been working on this for years and now is the right time to take the next step.’9

However, prison-based needle exchange has been an extremely contentious topic in Australia for many years, with prison staff and the Community and Public Sector Union representing them strongly opposing the introduction of an NSP on the basis they compromise staff safety.

The ACT union secretary stated in 2014 that the ACT prison would be ‘flooded’ with drug equipment,10 while the union’s deputy national president said the scheme would increase the risk to staff and inmates, facilitate the spread of blood borne viruses and significantly undermine rehabilitation efforts.11

In 2015, even with full government support, funding and supportive legislation, there is still no needle exchange program being officially run in the Alexander Maconochie Centre. There is certainly a needle and syringe program operating within the prison, it’s just an extremely dangerous one.

The opposition of prison staff around Australia to the idea of needle exchanges in prisons is symptomatic of the most important effect of criminalisation. That is, making some drugs illegal turns the people who use them into ‘criminals’.

People who use illicit drugs are therefore stigmatised for that behaviour alone.

It doesn’t matter if the person engages in no other criminal behaviour, has a good job, and in all ways is a ‘normal’, ‘decent’ member of the community, and it doesn’t matter to others how criminalisation affects the lives of the people who use those drugs; their use of that substance robs them of the implied rights, trust and respect that are afforded other people.

There are no laws or policies to protect people who use drugs from poor treatment or discrimination on the basis of their real or perceived drug use. This lack of legal protections, combined with issues such as poverty, homelessness, unemployment, and lack of education, to name a few, can create layers of disadvantage.

Criminalisation itself leads to effects such as:

- automatically creating a ‘criminal class’ of people who use or who have used drugs

- creating a black market of artificially inflated prices for substances so that people take great risks to obtain them or to obtain the money to buy them

- bringing people into contact with the criminal justice system

- creating social exclusion, driving people away from family, community, and social services

- leading to poverty and homelessness

- leading to people being dishonest when accessing services for fear of the reaction admitting to drug use might bring, leading in turn to substandard care and support

- reducing access to health services including harm reduction services

- allowing poor and inhumane treatment to go unnoticed and unreported.

People with a history of drug use sometimes internalise the stigma that is directed at them, believing themselves to be deserving of the poor treatment they receive when seeking support or even in everyday life.

They sometimes try to appear like ‘normal people’, that is, not like ‘typical junkies’ so that they can access the services they need.12

This process, however, does not always work. Even then, people with a history of drug use are unwilling to report cases of discrimination, and their attempts to ‘manage their image’ is seen as yet another example of the inherent dishonesty of people who use drugs.13

All of these factors work together to compound the marginalisation experienced by those who are unable to hide their drug use, and those who are seeking support. At the same time, many people tend to view people who use drugs as deserving of discrimination.

In fact, research commissioned by the Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League (AIVL) found that people in the general community believed that discrimination against people who use drugs was a good thing, because it would help them to stop using drugs.14

The evidence shows that people who use drugs are far less likely to use health services than other people in the community. They commonly experience discrimination in health services, and are then even more likely to stay away from these services.

Fear of punishment drives people underground, while support and lack of judgment have benefits that reach into every aspect of people’s lives.

The only country so far brave enough to decriminalise all drugs is Portugal. When that experiment first began, Portugal had rising levels of injecting drug use and some of the highest prevalence of HIV among people who inject drugs in Europe.

In more than ten years of decriminalisation, HIV transmissions have reduced dramatically, incarceration rates have reduced dramatically, and people who were initially strongly opposed to decriminalisation have become supporters.

More and more major organisations and more and more people with a range of experience are beginning to ask why more countries aren’t rejecting the failed war on drugs and trying their own experiments with drug policy.

Australia, once a leader in harm reduction, has fallen behind by staying still.

At a time when one of our closest neighbours, Indonesia, is showing no mercy to people convicted of drug crimes, shouldn’t we be showing the world we are again brave enough to follow the evidence to somewhere new?

References

1 Wilson, D., Kwon, A., Anderson, J., Thein, H., Law, M., Maher, L., et al. (2009). Return on investment 2: evaluating the cost-effectiveness of needle and syringe programs in Australia 2009. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra.

2 Cannabis is illegal in all states and territories of Australia, but possession of small amounts is decriminalised in the ACT and South Australia, and diversion programs are in place for minor offences in Victoria. It is up to the attending officer to decide whether to charge a person or whether to refer them to a diversion or education program, where those options are available.

However, across all jurisdictions, criminal charges for minor offences involving smaller amounts of cannabis possession are rare, as long as no violent offence is involved and depending to some extent on previous convictions.

3 Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League (AIVL). (2010). Hepatitis C Models of Access and Service Delivery for People with a History of Injecting Drug Use. AIVL, Canberra.

4 Iverson, J., Maher, L.(2014). Australian Needle and Syringe Program National Data Report 2009–2013. The Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

5 Harm Reduction International (HRI). (2012). Advocating for needle and syringe exchange programmes in prisons. Evidence and advocacy briefings series. HRI, London. Retrieved from: www.ihra.net

6 ibid.

7 ibid.

8 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2012). The health of Australia’s prisons. AIHW, Canberra. Retrieved from: www.aihw.gov.au

9 Westcott, B. (2012, 18 October). Breaking the syringe economy: prison union fights ACT plan. Retrieved from: www.crikey.com.au

10 McIlroy, T. (2014, 17 September). Stalemate over needle exchange hampering prison officers’ pay talks. The Canberra Times. Retrieved from: www.canberratimes.com.au

11 Water, A. (2014, 17 September). Needle exchange at AMC a fatally flawed proposal. The Canberra Times. Retrieved from: www.canberratimes.com.au

12 AIVL. (2010). op. cit. A process Carla Treloar describes as ‘image management’.

13 ibid.

14 Parr, V., Bullen, J. (2010). AIVL National Anti-Discrimination Project Qualitative Research Report. GfK Bluemoon for AIVL, Canberra. Retrieved from: www.nuaa.org.au