What AIDS 2014 can learn from Melbourne and what Melbourne can learn from the world

What AIDS 2014 can learn from Melbourne and what Melbourne can learn from the world

HIV Australia | Vol. 12 No. 2 | July 2014

By Michael Bartos

Nineteen eighty-four was a pivotal year for Melbourne’s AIDS response.

Nineteen eighty-four was a pivotal year for Melbourne’s AIDS response.From 1981 to 1983 there was a kind of ‘phoney war’ about AIDS in Australia. People kept up with the latest news from the US, but while some key gay community journalists and public health bureaucrats were preparing the way, for most Australians – including those among the gay community – AIDS still felt far away.

The first harbinger of a shift to a more urgent response came in mid-1983 with the formation of the AIDS action groups prompted by the Red Cross Blood Bank’s proposal to ban gay donors. But it was not until November 1984, when the ultra-conservative Queensland government decided to make political capital out of the HIV infection of four infants through blood from a gay donor, that the AIDS response really took hold.

Within a month, a full-scale emergency response was underway with many of the characteristics that continued to propel its success into the subsequent decade.

Thirty years on, many of the things we take for granted in today’s HIV response have become so commonplace it is hard to recall that they were the sites of struggle and heroic invention in the period of the mid-80s: safe sex for example, and even community involvement in a ‘medical’ issue.

A question of power

The key question that was defined in that period in Melbourne, and Australia more widely, was one of power – who was to control the AIDS response: paternalistic public health doctors or mobilised, affected communities?

In resolving this question largely in favour of communities, the practice of public health and health promotion was fundamentally changed, for the better.

Community had on its side fundamental political skills of organising – disciplined, sophisticated use of the media and viable, nuanced positions which were saleable to elected politicians.

Underlying these tactical strengths was a more basic shift in the balance of power through the ability of the community sector to reshape the notion of expertise.

This entailed a mastery of the traditional sources of expertise: gay community journalists became the most well-read HIV medical experts in the country, able to engage more traditionally medically-qualified experts on their own terms and often trumping them with more up-todate information obtained through international community networks.1

In addition to a strictly medical expertise, the capacity to speak for and be embedded in the communities most affected became recognised as a crucial aspect of the expertise necessary to the AIDS response. The struggle over control coalesced around two major elements: HIV testing, and the development of health promotion using culturally appropriate risk-reducing approaches.

Today, the mantra that HIV testing is the gateway to HIV prevention and care is so often heard that it is hard to even imagine that one of the most successful responses to HIV/AIDS in the epidemic’s history gained its initial power and leverage precisely through resisting testing.

One of the reasons the initial emergence of AIDS among gay men caused such moral and political panic was that gay men were not a readily identifiable group. The classic public health tools in response to an emerging communicable disease are screening and quarantine.

AIDS was identified as a singular disease rather than just random mortality because by the late 1970s communities of self-identifying gay men had emerged in Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco (among other places) and doctors serving these gay men – many themselves gay – noticed unusual patterns of disease and death.

It required self-identification because gay men’s risk was constituted by private sexual practice, not easily identified markers like race or specified geographic location.

Testing controversies

No test for gayness existed, but soon a test for HIV was developed and came into use in 1985 and Australia was one of the early adopters, at least for blood screening.

Once an HIV test became available, the issue was whether the population of gay men could be ‘flushed out’ by requiring them to test. Policies around antibody testing rapidly polarised, including within community organisations.

The AIDS Council of New South Wales was inclined to advocate in favour of testing, while the policy stance of the Victorian AIDS Council was that while individuals should be able to choose to test if they wished, there was no compelling reason in favour of testing – a position it maintained until around 1988 when clinical evidence and early results from the use of AZT suggested there were health benefits for those testing positive.2

The power over testing became a key point of leverage in getting community a seat at the public health table. Initially, the national and state bodies charged with responding to AIDS refused petitions for community representation.

In 1983 the National Health and Medical Research Council’s AIDS Task Force advised the Health Minister that ‘there was no place for representation of individuals who do not have the scientific understanding or discipline to contribute to the consideration of the issues on hand’.3

The introduction of compulsory notification of HIV infection in New South Wales and Queensland in 1985 ignited testing controversies, and the inclusion of mandatory testing in Victoria’s 1987 HIV legislation was only defeated after a concerted lobbying effort.

On one side, traditional public health authorities took testing as an article of faith. For them, surveillance was a necessary starting point for any response.

Gay community saw the issue differently: what was the use of testing if there was no effective treatment, if it exposed people to discrimination, and especially if testing undermined the solidarity between those infected and uninfected at a time when the community was inventing safe sex as a mass response.

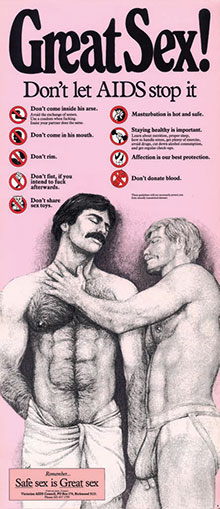

Displayed in gay clubs and saunas, this poster was part of the Victorian AIDS Council’s first education campaign, and one of the first safe sex posters devised by a non-government organisation in Australia. Image: Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives.

Displayed in gay clubs and saunas, this poster was part of the Victorian AIDS Council’s first education campaign, and one of the first safe sex posters devised by a non-government organisation in Australia. Image: Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives.Sex-positive

The invention of safe sex was the second significant realm of political struggle over AIDS in the mid- 1980s. The invention of safe sex has been widely canvassed, but it is worth recalling the salient features of Melbourne’s version.

In common with most, it was sex-positive, taking as a given that gay men should be supported to continue to enjoy sex. Exhortation to abstinence was considered unrealistic. In that sense, it was from the outset a risk-reduction rather than a risk-elimination strategy.

Once the debate over a single viral cause or multiple germ and lifestyle factors was settled with the discovery of HIV in mid-1984, consensus rapidly developed that the most important priority was to get gay men to use condoms for anal sex, regardless of HIV status.

Strategies such as reducing the number of partners, increasing the lighting in gay saunas (as proposed in San Francisco) or closing them altogether (New York), or opposing drug and alcohol use were dismissed as moralistic and hygenicist. A series of innovative HIV education efforts were put into effect by the Victorian AIDS Council in its first years (it was launched in December 1984).

The Council’s first education campaign included a poster which read, “Great Sex! Don’t let AIDS stop it” and a pamphlet titled AIDS: Trying to Reduce the Risk. Outreach activities were conducted in public places used for sex. A genre of sexually explicit ‘pornucation’ was created.4

Alcohol and drug use was addressed but not discouraged: instead, based on research that showed alcohol and drug use were part of intentional strategies to give internal ‘permission’ for unsafe sex, gay men were advised ‘alcohol and drugs: no excuse’.

Two boys kissing

Youth campaigns carefully courted controversy with a ‘two boys kissing’ poster driving recruitment into youth peer education groups. And by the end of the 1980s, HIV status was explicitly incorporated into HIV prevention programming with the appointment of an HIV-positive prevention officer and a 1992 campaign under the slogan ‘one of us has HIV, two of us have safe sex’.5

New HIV infections in Melbourne peaked in around 1985. They were largely among gay men. No doubt the simple fact of news about the presence of HIV accounted for some of the change in sexual practice that reduced transmission. But at the same time, an active, politically engaged mass response supported through community organising and in tune with changing norms must have made a major contribution.

2014 is not 1984. Political organising has taken a backseat to the business of AIDS, with the latter driven largely by increasing access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) across the world. In 2012 total international and domestic AIDS spending in all low and middleincome countries was around $19 billion, 53% of which came from domestic sources – the main source of recent spending growth since international aid increases stalled from 2009.6 In comparison, in 2012 the US alone spent $21.3 billion on its domestic HIV epidemic.7

The share of AIDS resources going to treatment has been steadily increasing, and that share will continue to increase through the inevitable logic of the cumulative cost of life-long therapy, especially as consensus suggests first-line ART costs have pretty much bottomed out.

Technology should not supplant the social

HIV prevention is not the same in the era of mass treatment access as it was before. But as Kippax and Race presciently argued a decade ago, the increasing place of medical technologies, whether testing or ART, do not supplant the social, they just change the ground over which social and sexual practice is negotiated.8

For much of the globe, community attempts to seize power over the AIDS response have been an uphill struggle. Development assistance has been a double-edged sword.

It has brought with it much needed resource assistance which has enabled millions of HIV infections to be averted and millions of lives to be prolonged through ART access (after the international aid community deemed in the early 2000s that it was prepared to fund treatment). But with the resources has come the dreaded development expert, inserting another layer of power getting in the way of local solutions to collective action problems.9

For many in the AIDS world, the turn to treatment has been embraced with a sense of relief that medical technologies can leave the messy business of politics behind. But this just blinkers out the real negotiations of power that happen on a macro scale when, for example, procurement contracts worth billions are negotiated out of sight, or on a micro scale as people negotiate the minefields of doctors’ instructions, neighbours’ contempt (or support) and the prospect of asking their new sexual partner to test him/herself for HIV.

The epidemic’s first decade was characterised by medicine’s impotence in the face of HIV and a humility that came with it. The third decade has been the opposite. Despite the measured restraint of the respective lead researchers, the last two International AIDS Conferences succumbed to an overblown medical triumphalism – in Vienna with the CAPRISA microbicide trial results, and in Washington with the continued over-selling of HPTN-05210 and treatment as prevention. In Melbourne, perhaps the weight of history will be able to exercise some counter-balance.

Michael Bartos was President of the Victorian AIDS Council from 1993–1994. He is currently UNAIDS Country Director in Zimbabwe.

References

1 Particularly notable in 1983 was the work of Adam Carr in Outrage and John Cozijn in Campaign.

2 See ‘Antibody testing’ in Victorian AIDS Council/Gay Men’s Health Centre (VAC/ GMHC). (2013). Under the Red Ribbon: Thirty Years of the Victorian AIDS Council/ Gay Men’s Health Centre. VAC/GMHC, Melbourne. Retrieved from: http://undertheredribbon.com.au and Jennifer Power. (2011). Movement, Knowledge, Emotion: Gay activism and HIV-AIDS in Australia. ANU Press, Canberra.

3 National Library of Australia, Greg Weir Archive. (1983). Doc. No: 123 – 9, Letter 1983.11.02, From: Blewett, N. Health Minister (Federal) To: Secretary Trades & Labor Council, Queensland: Outline of the Federal Government’s response to AIDS.

4 Leonard, W. (2012). Safe Sex and the Aesthetics of Gay Men’s HIV/AIDS Prevention in Australia: From Rubba Me in 1984 to F** k Me in 2009. Sexualities, 15(7), 834–849. doi:10.1177/1363460712454079

5 VAC/GMHC. (1993). A Dangerous Decade: Ten Years of the Victorian AIDS Council. VAC/GMHC, Melbourne. Retrieved from: www.vac.org.au

6 Kaiser Family Foundation and UNAIDS. (2013). Financing the Response to AIDS in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: International Assistance from Donor Governments in 2012, September 2013

7 See: aids.gov/federal-resources/funding-opportunities/how-were-spending

8 Kippax, S., Race, K. (2003). Sustaining safe practice: twenty years on. Social Science & Medicine, 57(1),1–12.

9 Booth D. (2012). Development as a collective action problem: addressing the real challenges of African governance. October 2012. Overseas Development Institute.

10 In May 2011, the HPTN 052 clinical trial conducted by the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) reported that antiretroviral medication reduced the risk of heterosexual transmission by 96%. Because of HPTN 052’s implications for the future response to the HIV epidemic, Science Magazine named this the scientific breakthrough of 2011. For further information see HPTN 052 – HPTN Studies: HIV Prevention Trials Network website. Retrieved from: www.hptn.org/research_studies/hptn052.asp